- Home

- David Yallop

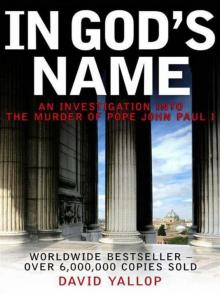

In God's Name Page 9

In God's Name Read online

Page 9

The book is a delight. Apart from providing an invaluable insight into the mind of Albino Luciani, each letter comments on aspects of modern life. Luciani’s unique ability to communicate, unique that is for an Italian Cardinal, is demonstrated again and again. The letters are also a clear proof of just how widely read Luciani was. Chesterton and Walter Scott receive a letter from the Patriarch, as do Goethe, Alessandro Manzoni, Marlowe and many others. There is even one addressed to Christ which begins in typical Luciani fashion.

Dear Jesus,

I have been criticized. ‘He’s a Bishop, he’s a Cardinal,’ people have said, ‘he’s been writing letters to all kinds of people: to Mark Twain, to Péguy, to Casella, to Penelope, to Dickens, to Marlowe, to Goldoni and heaven knows how many others. And not a line to Jesus Christ!

His letter to St Bernard grew into a dialogue, with the Saint giving sage advice, including an example of how fickle public opinion could be.

In 1815 the official French newspaper, Le Moniteur, showed its readers how to follow Napoleon’s progress: ‘The brigand flees from the island of Elba’; ‘The usurper arrives at Grenoble’; ‘Napoleon enters Lyons’; ‘The Emperor reaches Paris this evening’.

Into each letter is woven advice to his flock, on prudence, responsibility, humility, fidelity, charity. As a piece of work designed to communicate the Christian message it is worth twenty Papal encyclicals.

Spreading the ‘Good News’ was one aspect of Luciani’s years in Venice. Another was the recalcitrance constantly demonstrated by some of his priests. Apart from those who spent their time evicting tenants or complaining about having to sell Church treasures there were others who embraced Marxism as wholeheartedly as yet others were preoccupied with capitalism. One priest wrote in red paint across the walls of his Church, ‘Jesus was the first socialist’; another climbed into his pulpit in nearby Mestre and declared to his astonished congregation, ‘I shall do no more work for the Patriarch until he gives me a pay rise.’

Albino Luciani, a man with a highly developed sense of humour, was not amused at such antics. In July 1978 from the pulpit of the Church of the Redemptor in Venice he talked to his congregation of clerical error: ‘It is true that the Pope, bishops and priests do not cease to be poor men subject to errors and often we make errors.’

At this point he lifted his head from his manuscript and looking directly at the people said with complete sincerity:

‘I am convinced that when Pope Paul VI destined me to the See of Venice he committed an error.’

Within days of that comment Pope Paul VI died; at 9.40 pm on Sunday, August 6th, 1978. The throne was empty.

*At the time of Albino Luciani’s birth the village was called Forno di Canale. It was changed to Canale d’Agordo in 1964 at the instigation of Luciani’s brother, Edoardo. The village thus reverted to its original name.

*Here and throughout, monetary figures are expressed in values at the time in question.

*Richard Hamer, The Vatican Connection, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1982.

The Empty Throne

Within twenty-four hours of Paul’s death, with his body unburied and his Papacy unevaluated, Ladbrokes, the London bookmakers, had opened a book on the Papal election. The Catholic Herald, while carrying a front-page article criticizing the action, took care to let its readers know the current odds.

Cardinal Pignedoli was favourite at 5–2. Cardinals Baggio and Poletti were joint second favourites at 7–2, followed by Cardinal Benelli at 4–1. Also strongly fancied was Cardinal Willebrands at 8–1. Cardinal Koenig was quoted at 16–1. England’s Cardinal Hume was 25–1. These surprisingly long odds on the Englishman could perhaps be attributed to a statement Hume had made to the effect that he did not have the qualities for the job. Longest odds were quoted for Cardinal Suenens. Albino Luciani did not appear in the list of Papal runners.

Condemned by some for displaying lack of taste, Ladbrokes defended themselves by pointing out that with regard to the empty throne the ‘newspapers are full of speculation about front-runners, contenders and outsiders.’

Indeed the speculation had begun even before Pope Paul’s death. Peter Hebblethwaite, an ex-Jesuit priest converted to Vatican-watching, had asked in the Spectator on July 29th, ‘Who is running for Pope?’ He picked out three form horses to follow – Pignedoli, Baggio and Pironio. Whether Pope Paul had read Hebblethwaite’s comment that he ‘cannot be expected to live very much longer’ in his last few days, is not known.

The Italian media were a little slower off the mark. On the day after the Pope’s death the radio gave out nothing but Beethoven. On day two they relaxed a little with continuous Mozart. On day three there was a diet of light orchestral music. On day four the solemnity eased a little more with vocal renditions of ‘Moonlight Serenade’ and ‘Stardust’. Italian television for the first few days gave its viewers a variety of movies entirely peopled with nuns, Popes and cardinals.

Careful analysis of the English-speaking press covering the first few weeks of August 1978 indicates that if the 111 cardinals were as perplexed as the Vaticanologists then the Church was in for a long, confusing Conclave.

Followers of Hebblethwaite’s writings must have had a particularly hard time backing the winner. In the Sunday Times of August 13th, Cardinals Felici, Villot, Willebrands, Pellegrino and Benelli were added to his list of tips. The following Sunday he told his readers, ‘The new Pope: it could be Bertoli.’ The Sunday after that even Luciani got a mention. It was reminiscent of a racing correspondent reviewing the form for the Grand National or the Derby. If he mentioned every horse then after the race his paper could quote his comment about the winner.

A fish-seller in Naples had rather better luck. Using the numbers derived from the date of Pope Paul’s death, he won the national lottery.

Despite the pomp and ceremony, the funeral of the Pontiff was a curiously unemotional affair. It was as if his Papacy had ended long ago. After Humanae Vitae there had been no more Papal encyclicals and, apart from his courageous comments when his close friend, the former Prime Minister Aldo Moro, had been first kidnapped then murdered, there had been little from Paul over the past decade to inspire an outpouring of grief at his death: a man to respect, not one to love. There were many long and learned articles analyzing his Papacy in depth but if he is remembered at all by posterity it will be as the man who banned the Pill. It may be a cruel epitaph, an unfair encapsulation of a sometimes brilliant and often tortured mind, but what transpires in the marital bed is of more import to ordinary people than the fact that Paul flew in many aeroplanes, went to many countries, waved at many people and suffered agonies of mind.

In October 1975, Pope Paul had issued a number of rules which were to apply upon his death. One of these was that all cardinals in charge of departments of the Roman Curia would automatically relinquish their offices. This ensured that the Pope’s successor would have a completely free hand to make appointments. It also ensured during the period of sede vacante, between death and election, a considerable amount of nervous agitation. One of the few exceptions to this rule of automatic dismissal was the Camerlengo or Chamberlain. This office was held by Secretary of State Cardinal Jean Villot. Until the throne was filled, Villot became the keeper of the keys of Peter. During the vacancy the government of the Church was entrusted to the Sacred College of Cardinals who were obliged to hold daily meetings or ‘General Congregations’.

Another of the late Pope’s rules quickly became the subject of furious debate during the early General Congregations. Paul had specifically excluded from the Conclave that would elect his successor all cardinals over the age of eighty. Ottaviani mounted an angry attack on this rule. Supported by the 85-year-old Cardinal Confalonieri and the other over-eighties, they attempted to reverse it. Paul had fought many battles with this group. In death he won the last one. The cardinals voted to adhere to the rules. The General Congregation continued, on one occasion discussing for over an hour whether ballot papers should

be folded once or twice.

Rome was beginning to fill, but not with Italians – most of them were at the beaches. Apart from tourists the city was swarming with pressure groups, Vaticanologists, foreign correspondents, and the lunatic fringe. Part of this last group went around the city sticking up posters that proclaimed, ‘Elect a Catholic Pope’.

One of the ‘experts’ breathlessly informed Time Magazine, ‘I don’t know of one Italian cardinal who would feel happy voting for a foreigner’. He obviously did not know many Italian cardinals, certainly not the one who was Patriarch of Venice. Before leaving for Rome, Luciani had made it clear to former secretary Monsignor Mario Senigaglia, now officiating at the church of Santo Stefano, ‘I think the time is right for a Pope from the Third World’.

He also left no doubt whom he had in mind. Cardinal Aloisio Lorscheider, Archbishop of Fortaleza, Brazil. Lorscheider was widely regarded as a man possessed of one of the best minds in the modern Church. During his years in Venice, Luciani had come to know him well and as he confided to Senigaglia, ‘He is a man of faith and culture. Further than that he has a good knowledge of Italy and of Italian. Most important of all, his heart and mind are with the poor.’

Apart from their meetings in Italy, Luciani had spent a month with Lorscheider in Brazil in 1975. They had conversed in a variety of languages and discovered they had much in common. What was unknown to Luciani was the high regard that Lorscheider had for him. Lorscheider was later to observe of that month in Brazil, ‘On that occasion many people hazarded the guess that one day the Patriarch of Venice could become Pope.’

Driven to Rome by Father Diego Lorenzi, the man who had replaced Senigaglia as Secretary to the Patriarch two years previously, Luciani stayed at the Augustinian residence near St Peter’s Square. Apart from his attendance at the daily General Congregations he kept very much to himself, preferring to walk in the Augustinian gardens, quietly contemplating. Many of his colleagues led more strenuous lives: Ladbroke’s favourite, for example, Cardinal Pignedoli.

Pignedoli had been a close friend of the late Pope. Some Italian commentators cruelly observed he was the only friend Paul had. Certainly he appeared to be the only one to address him by the intimate ‘Don Battista’. In support of Pignedoli Cardinal Rossi of Brazil was at pains to remind the other cardinals of the tradition that Popes indicated who their successor should be and insisted that Pignedoli was ‘Paul’s best loved son’. Pignedoli was one of the most progressive of the Curial cardinals and hence disliked by most of the other Curial cardinals. He was cultured, well-travelled and, perhaps most important for his candidature, he had influenced either directly or indirectly the appointments of at least 28 of his brother cardinals.

Straightforward and honest running for the Vatican Throne is considered rather bad form in the higher reaches of the Roman Catholic Church. Candidates are not encouraged to stand up and announce publicly what their programme or platform will be. In theory there is no canvassing, no lobbying, no pressure group. In practice there is all of this and much more. In theory, the cardinals gather in secret Conclave and wait for the Holy Spirit to inspire them. As the hot August days went by, phone calls, secret meetings and pre-election promises ensured that the Holy Spirit was being given considerable worldly assistance.

One standard technique is for a candidate to state that he really does not think he measures up to the job. In this election run-up, that was said by a number with total sincerity, for example, Cardinal Basil Hume. Others made similar statements and would have been distressed if they had found their colleagues accepting them at their face value.

Attending afternoon tea on August 17th, Pignedoli declared to a gathering of Italian cardinals which went right across the spectrum of right, centre and left, that in spite of all the urgings and promptings he did not feel that he was suited for the Papacy. He suggested to his colleagues that they should vote instead for Cardinal Gantin. It was an imaginative suggestion.

Gantin, the black Cardinal of Benin, was 56 years of age. There was therefore very little chance of his election because of his relative youth. The ideal age was felt to be late 60s. Pignedoli was 68. Further, Gantin was black. Racialism is not confined to one side of the Tiber. Putting forward Gantin’s name could well attract votes for Pignedoli from the Third World whose cardinals held a vital 35 votes.

Pignedoli remarked that whoever was elected it should be done with all possible speed. Voting in the Conclave was to begin on the morning of August 26th, a Saturday. Pignedoli felt that it would be fitting if the new Pope was elected by the morning of Sunday 27th so that he could address the crowds at mid-day in a packed St Peter’s Square.

If there was a widespread desire among the cardinals for a quick resolution of the Conclave it would of course work greatly to the advantage of the candidate who entered with the largest following. Cardinals are just as susceptible to bandwagons as lesser mortals. To attain the Papacy Pignedoli knew that he had to look to the non-Curial cardinals to give him the 75 votes (two thirds plus one) essential for election. When the Curia had finished its internal fighting it would eventually focus on a specific candidate, preferably one of its own group. The pundits tossed a variety of Curial candidates into the air like demented jugglers – Bertoli, Baggio, Felici.

In a curious manoeuvre to assist his own candidature, Baggio contacted Paul Marcinkus and assured him that he would be confirmed in his post as Head of the Vatican Bank if Baggio were elected. Bishop Marcinkus, unlike the cardinals who had been dispossessed by the late Pope’s rules, was still running the Bank. There was no public indication that he would not continue to do so. The gesture by Baggio mystified Italian observers. If they had been able to persuade any of the cardinals present during the private General Congregations to talk, the move by Baggio would have taken on a deeper significance.

These meetings were giving very serious consideration to the problems facing the Church and to the possible solutions. In this manner Papal candidates emerge who are considered to have the abilities to implement the solutions. The August meetings were inevitably farranging. The concerns that emerged included discipline within the Church, evangelization, ecumenism, collegiality and world peace. There was another subject that occupied the minds of the cardinals: Church finances. Many were appalled that Marcinkus was still running the Vatican Bank after the Sindona scandal. Others wanted a full-scale investigation into Vatican finances. Cardinal Villot, as Secretary of State and Camerlengo, was obliged to listen to a long list of complaints which all had one common denominator, the name of Bishop Paul Marcinkus. This had been the reason for Baggio’s offer to keep him on in the job, an attempt to maintain the status quo and also a gambit to win the votes of such men as Cardinal Cody of Chicago, who would be perfectly content to let Marcinkus stay in his job.

The Cardinal from Florence, Giovanni Benelli, was another who preoccupied observers. As Paul’s troubleshooter he had made many enemies but it was freely acknowledged that he could influence at least fifteen voters.

To muddy the form book even further the fifteen very disgruntled old men who were about to be excluded from the actual Conclave began to bring pressure to bear on their colleagues. Their group, which contained some of the most reactionary men in the Vatican, predictably began to push for the Cardinal who they considered most completely represented their collective point of view, the Archbishop of Genoa Cardinal Giuseppe Siri. Siri had led the fight against many of the Second Vatican Council reforms. He had been the principal right-wing candidate in the Conclave which had elected Paul. Now a number of the over-age cardinals considered he was the ideal man for the chair of Peter. The octogenarians were not unanimous, however – at least one, Cardinal Carlo Confalonieri, was quietly singing the praises of Albino Luciani. Nevertheless the group as a whole thought Siri should be the next Pope.

Cardinal Siri claims that he is a much misunderstood man. During one sermon he had castigated women for wearing trousers and exhorted them to return to dresses, ‘so that t

hey could remember their true function on this earth’.

During the series of nine memorial Masses to Pope Paul, homilies were delivered by, among others, Cardinal Siri. The man who had blocked and obstructed Pope Paul at every turn pledged himself to the aims of the late Pontiff. The campaign for Siri went largely unnoticed by the Press. One of the arguments used by Siri’s supporters was that the next Pope must be an Italian. To insist that the next Pope be homegrown, even though only 27 of the voting cardinals out of a total of 111 were Italian, was typical of an attitude that abounds throughout the Vatican.

The belief that only an Italian Papacy can control not just the Vatican and the wider Church beyond but also Italy itself is deeply embedded in the thinking of the Vatican village. The last so-called ‘foreign’ Pope had been Adrian VI from Holland, in 522. This highly talented and scrupulously honest man became fully aware of the many evils that were flourishing in Rome. In an attempt to halt the rising tide of Protestantism in Germany he wrote to his Delegate in that country:

You are also to say that we frankly acknowledge that . . . for many years things deserving of abhorrence have gathered around the Holy See. Sacred things have been misused, ordinances transgressed, so that in everything there has been a change for the worse. Thus it is not surprising that the malady has crept down from the Head to the members, from the Popes to the hierarchy. We all, prelates and clergy, have gone astray from the right way . . . Therefore in our name give promises that we shall use all diligence to reform before all things, what is perhaps the source of all evil, the Roman Curia.

Within months of making that statement Pope Adrian was dead. Evidence suggests that he was poisoned by his doctor.

In God's Name

In God's Name