- Home

- David Yallop

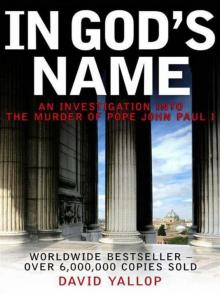

In God's Name Page 8

In God's Name Read online

Page 8

The question therefore remains unanswered. Who was the customer who ordered the counterfeit bonds? Based on all the available official evidence it is possible to draw only two conclusions. Each is bizarre. Leopold Ledl and Mario Foligni were planning to steal from the American Mafia a huge fortune in counterfeit bonds, having first conned the Mafia into going to the very considerable expense of creating the bonds. This particular section of the Mafia had a number of members who killed or maimed people who they merely imagined had insulted them. If this is the real reason then Ledl and Foligni were seeking an unusual form of suicide. The other conclusion is that the 950 million dollars’ worth of counterfeit bonds were destined for the Vatican.

In Venice, Albino Luciani continued to wear the robes that had been left by his predecessor, Cardinal Urbani. Throughout the entire period of his Patriarchship he refused to buy new ones, preferring instead to have the nuns who looked after him mend and re-mend. Indeed he wore the robes of Cardinal and Patriarch rarely, preferring his simple priest’s cassock.

His personal humility often created interesting situations. Motoring through Germany in 1975 with Father Senigaglia, the Cardinal arrived at the town of Aachen. Luciani particularly wanted to pray at a very ancient altar in the main church. Senigaglia watched as Luciani was told in rather a peremptory manner by the Church officials that the altar was closed and he should return another day. Back in the car Luciani translated the conversation he had had for Senigaglia’s benefit. Enraged, Senigaglia erupted from the car, ran to the church and gave the dignitaries a burst of Italian. They understood enough to know that he was declaring that the little priest they had turned away was the Patriarch of Venice. It was now Luciani’s turn to get angry with his secretary as he was almost dragged from the car by the German priests. As Luciani entered the church one of the still apologetic priests murmured to him, ‘Eminence, a little bit of red, at least, could be useful.’

On another occasion in Venice, Luciani was attending a conference on ecology. He became deeply involved in conversation with one of the participants. Wishing to continue the dialogue he invited the ecologist to call on him at his home. ‘Where do you live?’ asked the ecologist. ‘Just next door to St Mark’s,’ responded Luciani. ‘Do you mean the Patriarch’s Palace?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘And whom do I ask for?’ ‘Ask for the Patriarch.’

Underneath his humility and gentleness was a man who, by his environment and his vocation, was exceptionally strong. Neither to the left nor the right, he refused to become involved with the warring factions in Rome. The power plays inside the Vatican left Luciani on occasions puzzled as to why some of these men had become priests at all. In an Easter sermon of 1976 he observed:

Some are in the Church only as troublemakers. They are like the employee who first moved heaven and earth to get into the firm but once he had the job was perpetually restless and became a pestilential hair shirt on the skin of his colleagues and his superiors. Yes, some people seem only to look at the sun in order to find stains on it.

His desire to achieve a new synthesis by taking what in his view was right from both sides led him into considerable conflict in Venice. The issue of divorce is an example.

In Italy in the mid-1970s divorce was legal in the eyes of the State but unacceptable in the eyes of the Church. A move began to test the issue again through a referendum. Luciani was deeply opposed to the referendum simply because he was convinced it would split the Church and result in a majority committing themselves at the polling booths to a decision that the divorce laws should remain unchanged. If that happened it would be an official defeat for the Roman Catholic Church in the country it traditionally claimed as its own.

Benelli took the opposite view. He was convinced that the Church would win if there was a referendum.

The debate, not only within the Church but throughout Italy, reached an intense level. Shortly before the referendum took place, FUCI, a student group organized by a priest in Venice, sent a forty-page document to every bishop in the Veneto region. In it was a powerful argument supporting the pro-divorce position. Albino Luciani read the document carefully, considered for a while, then made national headlines by apparently disbanding the student group. In the Church it was seen by many as an act of courage. In the country commentators seized upon Luciani’s action as yet another example of the bigotry of the Catholic hierarchy.

What had outraged Luciani was not the pro-divorce statements but the fact that to buttress their arguments the group had quoted extensively from a wide variety of church authorities, leading theologians and a number of Vatican Council II documents. To use the latter in such a way was to Luciani a perversion of Church teaching. He had been there at the birth of Lumen Gentium, Gaudium et Spes and Dignitatis Humanae. Error might well have rights in the modern Church but in Venice 1974 for Luciani there was still a limitation to those rights. Thus to see a quotation from Dignitatis Humanae that extolled the rights of the individual ‘Protecting and promoting the inviolable rights of man is the essential duty of every civil power. The civil power must therefore guarantee to every citizen, through just laws and through other suitable means, the effective protection of religious liberty’, followed by the statement:

‘On other occasions the Church has found itself confronted by serious situations in society against which the only reasonable possibility was obviously not the use of repressive methods but the adoption of moral criteria and juridical methods which favoured the only good which was then historically possible: the lesser evil. Thus Christian morality adopted the theory of the just war; thus the Church allowed the legalization of prostitution (even in the Papal States), while obviously it remained forbidden on a moral level. And so also for divorce . . .’

To see such statements juxtaposed in a plea that the Church take a liberal view on divorce for the sake of expediency was unacceptable to Luciani. Obviously his beloved Vatican Council II teachings, like the Bible, could be taken to prove and justify any position. Luciani was aware that as he was head of the Bishops’ Council for the Veneto region, the Italian public would consider the statement official policy and then be faced with the dilemma of whether they should follow the bishops of the Veneto region or the bishops in the rest of Italy. In fact he did not disband the student group as is generally thought. He used a technique that was central to his philosophy. He firmly believed that you could radically alter power groups by identifying the precise centre of power and removing it. So he simply removed the priest who was advising the student group.

In reality, as Father Mario Senigaglia confirmed to me, Luciani’s personal view on divorce would have surprised his critics:

It was more enlightened than popular comment would have it. He could and did accept divorcees. He also easily accepted others who were living in what the Church calls ‘sin’. What outraged him was the biblical justification.

As Luciani had prophesied, the referendum resulted in a majority for the pro-divorce lobby. It left a split Church, a Pope who publicly expressed his amazement and incredulity at the result, and a dilemma for those who had to reconcile the differences between Church and State.

Luciani’s own dilemma was that he was committed to an unswerving obedience to the Papacy. Often the Pope would take a different position from that held by the Patriarch of Venice. When that position became public, Luciani felt it his duty publicly to support it. What he did on a one-to-one basis with members of his diocese frequently bore no resemblance to the Vatican line. By the mid-1970s he had moved even further towards a liberal position on birth control. This man, who upon the announcement of Humanae Vitae had allegedly declared ‘Rome has spoken. The case is closed,’ clearly felt that the case was far from closed.

When his young secretary Father Mario Senigaglia discussed with Luciani, with whom he had developed an almost father-son relationship, different moral cases involving parishioners, Luciani always approved the liberal view that Senigaglia took. Senigaglia said to me, ‘He was a very understanding man. Very many

times I would hear him say to couples. “We have made of sex the only sin when in fact it is linked to human weakness and frailty and is therefore perhaps the least of sins”.’

It is clear that Albino Luciani did not want for critics in Venice. Some considered that he revealed a nostalgia for the past rather than a desire for change. Some labelled him to the right, others to the left. Others saw his humility and gentleness as mere weakness. Perhaps posterity should judge the man on what he actually said rather than on what others thought he should have said.

On violence:

Strip God away from the hearts of men, tell children that sin is only a fairy tale invented by their grandparents to make them good, publish elementary school texts that ignore God and scoff at authority, and then don’t be surprised at what is happening. Education alone is not enough! Victor Hugo wrote that one more school means one less prison. Would that that were so today!

On Israel:

The church must also think of the Christian minorities who live in Arab countries. She cannot abandon them to fortune . . . for me personally, there is no doubt that a special tie exists between the people of Israel and Palestine. But the Holy Father, even if he wanted to, could not say that Palestine belongs to the Jews, since this would be to make a political judgment.

On nuclear weapons:

People say that nuclear weapons are too powerful and to use them would mean the end of the world. They are manufactured and accumulated, but only to ‘dissuade’ the enemy from attacking and to keep the international situation stable.

Look around. Is it true or not that for 30 years there has not been a world war?

Is it true or not that serious crises between the two great powers, the USA and the USSR have been avoided?

Let’s be happy over this partial result . . . A gradual, controlled and universal disarmament is possible only if an international organization with more efficient powers and possibilities for sanctions than the present United Nations comes into being and if education for peace becomes sincere.

On racism in the USA:

In the United States, despite the laws, Negroes are in practice on the edge of society. The descendants of the Indians have seen their situation bettered significantly only in recent years.

To call such a man a reactionary nostalgic may have validity. He yearned for a world that was not largely ruled by Communist philosophies, a world where abortion was not an every minute event. But if he was a reactionary he had some remarkably progressive ideas.

Early in 1976 Luciani attended yet another Italian Bishops’ Conference in Rome. One of the subjects openly discussed was the serious economic crisis Italy was then facing. Linked with this subject was another which the bishops discussed privately: the Vatican’s role in that economic crisis and the role of that good friend of Bishop Marcinkus, Michele Sindona. His empire had crashed in spectacular fashion. Banks were collapsing in Italy, Switzerland, Germany and the USA. Sindona was wanted by the Italian authorities on a range of charges and was fighting his extradition from the United States. The Italian Press had asserted that the Vatican had lost in excess of 100 million dollars. The Vatican had denied this but admitted that it had sustained some loss. In June 1975 the Italian authorities, while continuing their fight to bring Sindona to justice had sentenced him in absentiato to a prison term of three-and-a-half years, the maximum they could give for the offences. Many bishops felt that Pope Paul VI should have moved Marcinkus from the Vatican Bank when the Sindona bubble burst in 1974. Now, two years later, Sindona’s friend was still controlling the Vatican Bank.

Albino Luciani left Rome, a city buzzing with speculation about how many millions the Vatican had lost in the Sindona affair, left a Bishops’ Conference where the talk had been of how much the Vatican Bank owned of Banca Privata, of how many shares the Bank had in this conglomerate or that company. He returned to Venice where the Don Orione School for the handicapped did not have enough money for school books.

Luciani went to his typewriter and wrote a letter which was published in the next edition of the diocese magazine. It was entitled ‘A loaf of bread for the love of God’. He began by appealing for money to help the victims of a recent earthquake disaster in Guatemala, stating that he was authorizing a collection in all churches on Sunday, February 29th. He then commented on the state of economic affairs in Italy, advising his readers that the Italian bishops and their ecclesiastical communities were committed to showing practical signs of understanding and help. He went on to deplore:

The situation of so many young people who are looking for work and cannot find it. Of those families who are experiencing the drama or prospect of sacking. Those who have sought security by emigrating far away and who now find themselves confronted by the prospect of an unhappy return. Those who are old and sick and because of the insufficiency of social pensions suffer worst the consequences of this crisis . . .

I wish priests to remember and frequently to refer in any way they like to the situation of the workers. We complain sometimes that workers go and seek bad advice from the left and the right. But in reality how much have we done to ensure that the social teaching of the Church can be habitually included in our Catechism, in the hearts of Christians?

Pope John asserted that workers must be given the power to influence their own destiny at all levels, even the highest scale. Have we always taught that with courage? Pius XII while on the one hand warning of the dangers of Marxism, on the other hand reproves those priests who remain uncertain in face of that economic system which is known as capitalism, the grave consequences of which the Church has not failed to denounce. Have we always listened to this?

Albino Luciani then gave an extraordinary demonstration of his own abhorrence of a wealthy, materialistic Church. He exhorted and authorized all of his parish priests and rectors of sanctuaries to sell their gold, necklaces, and precious objects. The proceeds were to go to the Don Orione centre for handicapped people. He advised his readers that he intended to sell the bejewelled cross and gold chain which had belonged to Pius XII and which Pope John had given to Luciani when he had made him a bishop.

It is very little in terms of the money it will produce but it is perhaps something if it helps people to understand that the true treasures of the Church are, as St Lorenzo said, the poor, the weak who must be helped not with occasional charity but in such a way that they can be raised a little at a time to that standard of life and that level of culture to which they have a right.

He also announced that he intended to sell to the highest bidder a valuable pectoral cross with gold chain and the ring of Pope John. These items had been given to Venice by Pope Paul during his September visit of 1972. Later in the same article he quoted two Indians. Firstly, Gandhi: ‘I admire Christ but not Christians.’

Luciani then expressed the wish that the words of Sandhu Singh would perhaps one day no longer be true:

One day I was sitting on the banks of a river. I took from the water a round stone and I broke it. Inside it was perfectly dry. That stone had been lying in the water for a very long time but the water had not penetrated it. Then I thought that the same thing happened to men in Europe. For centuries they have been surrounded by Christianity but Christianity has not penetrated, does not live within them.

The response was mixed. Some of the Venetian priests had grown attached to the precious jewels they had in their churches. Luciani also came under attack from some of the traditionalists of the city, those who were fond of recalling the glory and power that was interwoven in the title of Patriarch, the last vestige of the splendour of the Serenissima. This man who was pledged to seeking out and living the essential, eternal truth of the Gospel met a deputation of such citizens in his office. Having listened to them he said:

I am first a bishop among bishops, a shepherd among shepherds, who must have as his first duty the spreading of the Good News and the safety of his lambs. Here in Venice I can only repeat what I said at Canale, at Belluno and at Vittorio Venet

o.

Then he phoned the fire brigade, borrowed a boat and went to visit the sick in a nearby hospital.

As already recorded, one of the methods this particular shepherd employed to communicate with his flock was the pen. On more than one occasion Luciani told his secretary that if he had not become a priest he would probably have become a journalist. To judge by his writings he would have been an asset to the profession. In the early 1970s he devised an interesting technique to make a variety of moral points to the readers of the diocesan magazine: a series of letters to a variety of literary and historical characters. The articles caught the eye of the editor of a local newspaper, who persuaded Luciani to widen his audience through the paper. Luciani reasoned that he had more chance of spreading the ‘Good News’ through the press than he did preaching to half-empty churches. Eventually a collection of the letters was published in book form, Illustrissimi – the most illustrious ones.

In God's Name

In God's Name