- Home

- David Yallop

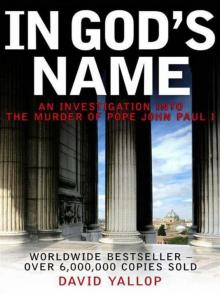

In God's Name Page 5

In God's Name Read online

Page 5

Ottaviani contacted the four dissenting priests from the Pontifical Commission. Their views had already been fully incorporated within the Commission’s report. He persuaded them to enlarge their dissenting conclusions in a special report. Thus the Jesuit Marcellino Zalba, the Redemptorist Jan Visser, the Franciscan Ermenegildo Lio and the American Jesuit John Ford, created a second document.

No matter that in doing so they acted in an unethical manner; the object of the exercise was to give Ottaviani a weapon to brandish at the Pope. The four men bear an awesome responsibility for what was to follow. The amount of death, misery and suffering that directly resulted from the final Papal decision can to a large degree be laid directly at their feet. An indication of the thought-processess applied by these four can be gauged from one of their number, the American Jesuit, John Ford. He considered he was in direct contact with the Holy Spirit with regard to this issue and that this Divine guidance had led him to the ultimate truth. If the majority view prevailed, Ford declared that he would have to leave the Roman Catholic Church. This minority report represents the epitome of arrogance. It was submitted to Pope Paul along with the official Commission report. What followed was a classic illustration of the ability of a minority of the Roman Curia to control situations, to manipulate events. By the time the two reports were submitted to Paul most of the 68 members of the Commission were scattered to the corners of the earth.

Convinced that this difficult problem had finally been resolved with a liberalizing conclusion the majority of the Commission members waited in their various countries for the Papal announcement approving artificial birth control. Some of them began to prepare a paper that could serve as an introduction or preface to the impending Papal ruling, in which there was full justification for the change in the Church’s position.

Throughout 1967 and continuing into early 1968 Ottaviani capitalized on the absence from Rome of the majority of the Commission. Those who were still in the City were exercising great restraint in not bringing further pressure upon Paul. By doing so they played straight into Ottaviani’s hands. He marshalled members of the old guard who shared his views. Cardinals Cicognani, Browne, Parente and Samore, daily just happened to meet the Pope. Daily they told him that to approve artificial birth control would be to betray the Church’s heritage. They reminded him of the Church’s Canon Law and the three criteria that were applied to all Catholics seeking to marry. Without these three essentials the marriage is invalidated in the eyes of the Church: erection, ejaculation and conception. To legalize oral contraception, they argued, would be to destroy that particular church Law. Many, including his predecessor John XXIII, have compared Pope Paul VI with the doubt-racked Hamlet. Every Hamlet has need of an Elsinore Castle in which to brood. Eventually, the Pope decided that he and he alone would make the final decision. He summoned Monsignor Agostino Casaroli and advised him that the problem of birth control would be removed from the competence of the Holy Office. Then he retired to Castel Gandolfo to work upon the encyclical.

On the Pope’s desk at Castel Gandolfo, amid the various reports, recommendations and studies on the issue of artificial birth control, was one from Albino Luciani.

While his Commissions, consultants and Curial cardinals were dissecting the problem the Pope had also asked for the opinion of various regions in Italy. One of these was the Veneto diocese. The Patriarch of Venice, Cardinal Urbani, had called a meeting of all the bishops within the region. After a day’s debate it was decided that Luciani should draw up the report.

The decision to give Luciani the task was largely based on his knowledge of the problem. It was a subject he had been studying for a number of years. He had talked and written about it, he had consulted doctors, sociologists, theologians, and not least that group who had personal practical experience of the problem, married couples.

Among the married couples was his own brother, Edoardo, struggling to earn enough to keep an ever-growing family that eventually numbered ten children. Luciani saw at first hand the problems posed by a continuing ban on artificial birth control. He had grown up surrounded by poverty. Now in the late 1960s there appeared to him to be as much poverty and deprivation as in the lost days of his youth. When those one cares for are in despair because of their inability to provide for an increasing number of children, one is inclined to view the problem of birth control in a different light from Jesuits who are in direct contact with the Holy Spirit.

The men in the Vatican could quote Genesis until the Day of Judgment but it would not put bread on the table. To Albino Luciani Vatican Council II had intended to relate the Gospels and the Church to the twentieth century, and to deny men and women the right of artificial birth control was to plunge the Church back to the Dark Ages. Much of this he said quietly and privately as he prepared his report. Publicly he was acutely aware of his obedience to the Pope. In this Luciani remained an excellent example of his time. When the Pope decreed then the faithful agreed. Yet even in his public utterances there are clear clues to his thinking on the issue of birth control.

By April 1968, after much further consultation, Luciani’s report had been written and submitted. It had met with the approval of the bishops of the Veneto region and Cardinal Urbani had duly signed the report and sent it directly to Pope Paul. Subsequently, Urbani saw the document on the Pope’s desk at Castel Gandolfo. Paul advised Urbani that he valued the report greatly. So highly did he praise it that when Urbani returned to Venice he went via Vittorio Veneto to convey directly to Luciani the Papal pleasure the report had given.

The central thrust of the report was to recommend to the Pope that the Roman Catholic Church should approve the use of the anovulant pill developed by Professor Pincus. That it should become the Catholic birth control pill.

On April 13th, Luciani talked to the people of Vittorio Veneto about the problems the issue was causing. With the delicacy that had by now become a characteristic Luciani hallmark, he called the subject ‘conjugal ethics’. Having observed that priests in speaking and in hearing confessions ‘must abide by the directives given on several occasions by the Pope until the latter makes a pronouncement’, Luciani went on to make three observations:

1 It is easier today, given the confusion caused by the press, to find married persons who do not believe that they are sinning. If this should happen it may be opportune, under the usual conditions, not to disturb them.

2 Towards the penitent onanist, who shows himself to be both penitent and discouraged, it is opportune to use encouraging kindness, within the limits of pastoral prudence.

3 Let us pray that the Lord may help the Pope to resolve this question. There has never perhaps been such a difficult question for the Church: both for the intrinsic difficulties and for the numerous implications affecting other problems, and for the acute way in which it is felt by the vast mass of the people.

Humanae Vitae was published on July 25th, 1968. Pope Paul had Monsignor Lambruschini of the Lateran University explain its significance to the Press, in itself a rather superfluous exercise. More significantly, it was stressed that this was not an infallible document. It became for millions of Catholics an historic moment like the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Years later they knew exactly what they were doing and where they were when the news reached them.

On a disaster scale for the Roman Catholic Church it measures higher than the treatment of Galileo in the seventeenth century or the declaration of Papal Infallibility in the nineteenth. This document which was intended to strengthen Papal authority had precisely the opposite effect.

This celibate man, then 71 years of age, having expanded the Commission that was advising him on the problem of birth control, ignored its advice. He declared that the only methods of birth control which the Church considered acceptable were abstinence and the rhythm method ‘. . . in any use whatever of marriage there must be no impairment of its natural capacity to procreate human life.’

Millions ignored the Pope and continued t

o practise their faith and use the Pill or whatever other method they found most suitable. Millions lost patience and faith. Others shopped around for a different priest to whom to confess their sins. Still others tried to follow the encyclical and discovered they had avoided one Catholic concept of sin only to experience another, divorce. The encyclical totally divided the Church.

‘I cannot believe that salvation is based on contraception by temperature and damnation is based on rubber,’ declared Dr Andre Hellegers, an obstetrician and member of the ignored Pontifical Commission. One surprising line of the Vatican’s defence came from Cardinal Felici: ‘The possible mistake of the superior [the Pope] does not authorize the disobedience of subjects.’

Albino Luciani read the encyclical with growing dismay. He knew the uproar that would now engulf the Church. He went to his church in Vittorio Veneto and prayed. There was no question in his mind but that he must obey the Papal ruling but, deep as his allegiance to the Pope was, he could not, would not, merely sing praise to Humanae Vitae. He knew a little of what the document must have cost the Pope; he knew a great deal of what it was going to cost the faithful who would have to attempt to apply it to their everyday lives.

Within hours of reading the encyclical Luciani had written his response to the diocese of Vittorio Veneto. In ten years’ time when he became Pope, the Vatican would assert that Luciani’s response was ‘Rome has spoken. The case is closed.’ It was yet another Vatican lie. Nothing approaching that sentiment appears in his words. He began by reminding the diocese of his comments in April, then continued:

I confess that, although not revealing it in what I wrote, I privately hoped that the very grave difficulties that exist could be overcome and the response of the Teacher, who speaks with special charisma and in the name of the Lord, might coincide, at least in part, with the hopes of many married couples after the setting up of a relevant Pontifical Commission to examine the question.

He acknowledged the amount of care and consideration the Pope had given to the problem and said that the Pope knew ‘he is about to cause bitterness in many’, but he continued, ‘The old doctrine, presented in a new framework of encouraging and positive ideas about marriage and conjugal love, better guarantees the true good of man and family.’ Luciani faced some of the problems that would inevitably flow from Humanae Vitae:

The thoughts of the Pope, and mine, go especially to the sometimes grave difficulties of married couples. May they not lose heart, for goodness sake. May they remember that for everyone the door is narrow and narrow the road that leads to life (cf Matt 7:14). That the hope of the future life must illuminate the path of Christian couples. That God does not fail to help those who pray to Him with perseverance. May they make the effort to live with wisdom, justice and piety in the present time, knowing that the fashion of this world passes away (cf 1 Cor 7:31) . . . ‘And if sin should still have a hold on them, may they not be discouraged, but have recourse with humble perseverance to God’s mercy through the sacrament of Penance’.

This last quotation, direct from Humanae Vitae, had been one of the few crumbs of comfort for men like Luciani who had hoped for a change. Trusting that he had his flock with him in a ‘sincere adhesion to the teaching of the Pope’, Luciani gave them his blessing.

Other priests in other countries took a more openly hostile line. Many left the priesthood. Luciani steered a more subtle course.

In January 1969 he returned yet again to this subject that the Vatican would have him make a one-line dogmatic pronouncement upon. He was aware that some of his priests were denying absolution to married couples using the contraceptive pill and that other priests were readily absolving what Pope Paul had deemed a sin. Dealing with this problem Luciani quoted the response from the Italian Bishops’ Conference to Humanae Vitae. It was a response he had helped to draft. In it priests were recommended to show ‘evangelical kindness’ towards all married people, but especially, as Luciani pointed out, towards those ‘whose failings derive . . . from the sometimes very serious difficulties in which they find themselves. In that case the behaviour of the spouses, although not in conformity with Christian norms, is certainly not to be judged with the same gravity as when it derives from motives corrupted by selfishness and hedonism.’ Luciani also admonished his troubled people not to feel ‘an anguished, disturbing guilt complex’.

Throughout this entire period the Vatican continued to benefit from the profits derived from one of the many companies it owned, the Istituto Farmacologico Sereno. One of Sereno’s best selling products was an oral contraceptive called Luteolas.

The loyalty Albino Luciani had demonstrated in Vittorio Veneto was not lost on the Holy Father in Rome. Better than most the Pope knew that such loyalty had been achieved at a heavy price. The document on his desk that bore Cardinal Urbani’s signature, but was in essence Luciani’s position on birth control, was mute testimony to the personal cost.

Deeply impressed, Pope Paul VI observed to his Under-Secretary of State, Giovanni Benelli, ‘In Vittorio Veneto there is a little bishop who seems well suited to me.’ The astute Benelli went out of his way to establish a friendship with Luciani. It was to prove a friendship with far-reaching consequences.

Cardinal Urbani, Patriarch of Venice, died on September 17th, 1969. The Pope remembered his little bishop. To Paul’s surprise Luciani politely declined what many saw as a glittering promotion. Entirely without ambition he was happy and content with his work in Vittorio Veneto.

Pope Paul cast his net farther. Cardinal Antonio Samore, as reactionary as his mentor Ottaviani, became a strong contender. Murmurings of discontent from members of the Venetian laity, declaring they would be happier if Samore remained in Rome, reached the Pope’s ears.

Pope Paul then gave yet another demonstration of the Papal dance he had invented since ascending to the throne of Peter: one step forward, one step back – Luciani, Samore, Luciani.

Luciani began to feel the pressure from Rome. Eventually he succumbed. It was a decision he regretted within hours. Unaware that its new Patriarch had fought against accepting the position, Venice celebrated the fact that ‘local man’ Albino Luciani was appointed on December 15th, 1969.

Before leaving Vittorio Veneto, Luciani was presented with a donation of one million lire. He quietly declined the gift and after suggesting that the people should donate it to their own personal charities reminded them what he had told his priests when he had arrived in the diocese eleven years earlier: ‘I came without five lire. I want to leave without five lire.’ Albino Luciani took with him to Venice a small pile of linen, a few sticks of furniture and his books.

On February 8th, 1970, the new Patriarch, now Archbishop Luciani, entered Venice. Tradition decreed that the entry of a new Patriarch be a splendid excuse for a gaily bedecked procession of gondolas, brass bands, parades and countless speeches. Luciani had always had an intense dislike of such pomp and ceremony. He cancelled the ritual welcome and confined himself to a speech during which he referred not only to the historic aspects of the city but acknowledged that his diocese also contained industrial areas such as Mestre and Marghera. ‘This was the other Venice,’ Luciani observed, ‘with few monuments but so many factories, houses, spiritual problems, souls. And it is to this many-faceted city that Providence now sends me. Signor Mayor, the first Venetian coins, minted as long ago as A.D. 850, had the motto “Christ, save Venice”. I make this my own with all my heart and turn it into a prayer, “Christ, bless Venice”.’

The pagan city was in dire need of Christ’s blessing. It was bulging with monuments and churches that proclaimed the former glories of an imperial republic, yet Albino Luciani rapidly learned that the majority of the churches within the 127 parishes were continually nearly empty. If one discounted the tourists, the very young and the very old, then church attendance was appallingly low. Venice is a city that has sold its soul to tourism.

The day after his arrival, accompanied by his new secretary, Father Mario Senigaglia, he

was at work. Declining invitations to attend various soirées, cocktail parties and receptions, he visited instead the local seminary, the women’s prison of Giudecca, the male prison of Santa Maria Maggiore, then celebrated Mass in the Church of San Simeone.

It was customary for the Patriarch of Venice to have his own boat. Luciani had neither the personal wealth nor the inclination for what seemed to him an unnecessary extravagance. When he wanted to move through the canals he and Father Mario would catch a water bus. If it was an urgent appointment Luciani would telephone the local fire brigade, the carabinieri or the finance police and beg the loan of one of their boats. Eventually the three organizations worked out a roster to oblige the unusual priest.

During a national petrol crisis the Patriarch took to a bicycle when visiting the mainland. Venetian high society shook its head and muttered disapprovingly. Many of them enjoyed the pomp and ceremony they associated with the Patriarchship. To them a Patriarch was an important person to be treated in an important manner. When Albino Luciani and Father Mario appeared unannounced at a hospital to visit the sick they would immediately be surrounded by the administrators, doctors, monks and nuns. Father Senigaglia recalled for me such an occasion.

‘I don’t want to take up your precious time. I can go round on my own.’

‘Not a bit of it, Your Eminence, it’s an honour for us.’

Thus a large procession would begin to make its way through the wards with an increasingly discomfited Luciani. Eventually he would say, ‘Well, perhaps it’s better if I come back another time, it’s already late.’

He would effect several false exits in an attempt to shake off the entourage; without success.

‘Don’t worry, Your Eminence. It’s our duty.’

Outside he would turn to Father Senigaglia, ‘But are they always like this? It’s a shame. I am used to something different. Either we shall have to make them understand or I shall lose a good habit.’

In God's Name

In God's Name