- Home

- David Yallop

In God's Name Page 2

In God's Name Read online

Page 2

I am sure that the fact that I recount conversations between men dead before my investigation began will be cause for comment. How for example could I know what passed between Pope John Paul I and Cardinal Jean Villot on the day they discussed the issue of birth control? Within the Vatican there is no such thing as a private audience that remains completely private. Quite simply both men subsequently talked to others of what had transpired. These secondary sources, sometimes with deeply differing personal opinions on the issue discussed by the Pope and his Secretary of State, provided the words attributed. Therefore while the dialogue within this book is reconstructed, it is not fabricated.

Prologue

The spiritual leader of nearly one-fifth of the world’s population wields immense power: but any uninformed observer of Albino Luciani at the beginning of his reign as Pope John Paul I would have found it difficult to believe that this man truly embodied such power. The diffidence and humility emanating from this small, quiet, 65-year-old Italian had led many to conclude that this Papacy would not be particularly noteworthy. The well-informed, however, knew differently: Albino Luciani had embarked on a revolution.

On September 28th, 1978 he had been Pope for thirty-three days. In little more than a month he had initiated various courses of action which, if completed, would have a direct and dynamic effect upon us all. The majority in this world would applaud his decisions, a minority would be appalled. The man who had quickly been labelled ‘The Smiling Pope’ intended to remove the smiles from a number of faces on the following day.

That evening Luciani sat down to dinner in the third-floor dining-room of the Apostolic Palace within Vatican City. With him were his two secretaries, Father Diego Lorenzi, who had worked closely with him in Venice for over two years when, as a Cardinal, Luciani had been Patriarch there, and Father John Magee, newly acquired since the Papal election. As the nuns who worked in the Papal Apartments hovered anxiously, Albino Luciani ate a frugal meal of clear soup, veal, fresh beans and a little salad. He sipped occasionally from a glass of water and considered the events of the day and the decisions he had made. He had not wanted the job. He had not sought or canvassed for the Papacy. Now as Head of State the awesome responsibilities were his.

While Sisters Vincenza, Assunta, Clorinda and Gabrietta quietly served the three men as they watched on television the events which preoccupied Italy that evening, other men in other places were being caused deep anxiety by the activities of Albino Luciani.

One floor below the Papal Apartments the lights were still on in the Vatican Bank. Its head, Bishop Paul Marcinkus, had other more pressing problems on his mind than his evening meal. Chicago-born Marcinkus had learned about survival on the back-streets of Cicero, Illinois. During his meteoric rise to the position of ‘God’s Banker’ he had survived many moments of crisis. Now he was confronted with the most serious he had ever faced. In the past thirty-three days his colleagues in the Bank had noticed a remarkable change in the man who controlled the Vatican’s millions. The 6ft 3in, 16-stone extrovert had become moody and introspective. He was visibly losing weight and his face had acquired a grey pallor. Vatican City in many respects is a village and secrets are hard to keep in a village. Word had reached Marcinkus that the new Pope had quietly begun his own personal investigation of the Vatican Bank and specifically into the methods Marcinkus was using to run that Bank. Countless times since the arrival of the new Pope, Marcinkus had regretted that business in 1972 concerning the Banca Cattolica del Veneto.

Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Jean Villot was another who was still at his desk on that September evening. He studied the list of appointments, resignations to be asked for, and transfers which the Pope had handed to him one hour previously. He had advised, argued, remonstrated but to no avail. Luciani had been adamant.

It was by any standards a dramatic reshuffle. It would set the Church in new directions; directions which Villot, and the others on the list who were about to be replaced, considered highly dangerous. When these changes were announced there would be millions of words written and uttered by the world’s media, analyzing, dissecting, prophesying, explaining. The real explanation, however, would not be discussed, would not be given a public airing – there was one common denominator, one fact that linked each of the men about to be replaced. Villot was aware of it. More important, so was the Pope. It had been one of the factors that had caused him to act: to strip these men of real power and put them into relatively harmless positions. It was Freemasonry.

The evidence the Pope had acquired indicated that within the Vatican City State there were over 100 Masons, ranging from Cardinals to priests. This despite the fact that Canon Law stated that to be a Freemason ensured automatic excommunication. Luciani was further preoccupied with an illegal masonic lodge which had penetrated far beyond Italy in its search for wealth and power. It called itself P2. The fact that it had penetrated the Vatican walls and formed masonic links with priests, bishops and even Cardinals made P2 anathema to Albino Luciani.

Villot had already become deeply concerned about the new Papacy before this latest bombshell. He was one of the very few who was aware of the dialogue taking place between the Pope and the State Department in Washington. He knew that on October 23rd the Vatican would be receiving a Congressional delegation, and that on October 24th the delegation would be having a private audience with the Pope. The subject: birth control.

Villot had looked carefully at the Vatican dossier on Albino Luciani. He had also read the secret memorandum that Luciani, then Bishop of Vittorio Veneto, had sent to Paul VI before the Papal announcement of the encyclical Humanae Vitae, an encyclical which prohibited Catholics using any artificial form of birth control. His own discussions with Luciani had left him in no doubt where the new Pope stood on this issue. Equally, in Villot’s mind, there was no doubt what Paul’s successor was now planning to do. There was to be a dramatic change of position. Some would agree with Villot’s view that it was a betrayal of Paul VI. Many would acclaim it as the Church’s greatest contribution to the twentieth century.

In Buenos Aires, another banker, Roberto Calvi, had Pope John Paul I on his mind as September 1978 drew to a close. In the preceding weeks he had discussed the problems posed by the new Pope with his protectors, Licio Gelli and Umberto Ortolani, two men who could list among their many assets their complete control of Calvi, chairman of Banco Ambrosiano. Calvi had been beset with problems even before the Papal election that placed Albino Luciani upon St Peter’s chair. The Bank of Italy had been secretly investigating Calvi’s Milan bank since April. It was an investigation prompted by a mysterious poster campaign against Calvi which had erupted in late 1977: posters which gave details of some of Calvi’s criminal activities and hinted at a world-wide range of criminal acts.

Calvi was aware of exactly what progress the Bank of Italy was making with its investigation. His close friendship with Licio Gelli ensured a day-by-day account of it. He was equally aware of the Papal investigation into the Vatican Bank. Like Marcinkus he knew it was only a matter of time before the two independent investigations realized that to probe one of these financial empires was to probe both. He was doing everything within his considerable power to thwart the Bank of Italy and protect his financial empire, from which he was in the process of stealing over one billion dollars.

Careful analysis of Roberto Calvi’s position in September 1978 makes it abundantly clear that if Pope Paul was succeeded by an honest man then Calvi faced total ruin, the collapse of his bank and certain imprisonment. There is no doubt whatever that Albino Luciani was just such a man.

In New York, Sicilian banker Michele Sindona had also been anxiously monitoring Pope John Paul’s activities. For over three years Sindona had been fighting the Italian Government’s attempts to have him extradited. They wanted him brought to Milan to face charges involving fraudulent diversion of 225 million dollars. Earlier that year, in May, it appeared that Sindona had finally lost the long battle. A Federal Judg

e had ruled that the extradition request should be granted.

Sindona remained on a 3 million dollar bail while his lawyers prepared to play one last card. They demanded that the United States Government prove that there was well-founded evidence to justify extradition. Sindona asserted that the charges brought against him by the Italian Government were the work of Communist and other left-wing politicians. His lawyers also asserted that the Milan prosecutor had concealed evidence that would clear Sindona and that if their client was returned to Italy he would almost certainly be assassinated. The hearing was scheduled for November.

That summer, in New York, others were equally active on behalf of Michele Sindona. One Mafia member, Luigi Ronsisvalle, a professional killer; was threatening the life of witness Nicola Biase, who had earlier given evidence against Sindona in the extradition proceedings. The Mafia also had a contract out on the life of assistant United States attorney John Kenney, who was Chief Prosecutor in the extradition proceedings. The fee being offered for the murder of the Government attorney was 100,000 dollars.

If Pope John Paul I continued to dig into the affairs of the Vatican Bank then no amount of Mafia contracts would help Sindona in his fight against being returned to Italy. The web of corruption at the Vatican Bank, which included the laundering of Mafia money through that Bank, went back beyond Calvi: back to Michele Sindona.

In Chicago another Prince of the Catholic Church worried and fretted about events in the Vatican City: Cardinal John Cody, head of the richest archdiocese in the world. Cody ruled over two-and-a-half million Catholics and nearly 3,000 priests, over 450 parishes and an annual income that he refused to reveal in its entirety to anyone. It was in fact in excess of 250 million dollars. Fiscal secrecy was only one of the problems that whirled around Cody. By 1978 he had ruled Chicago for thirteen years. In those years the demands for his replacement had reached extraordinary proportions. Priests, nuns, lay workers, people from many secular professions had petitioned Rome in their thousands for the removal of a man they regarded as a despot.

Pope Paul had agonized for years about removing Cody. He had on at least one occasion actually steeled himself and made the decision, only to revoke the order at the last moment. The complex, tortured personality of Paul was only part of the reason for the vacillation. Paul knew that other secret allegations had been made against Cody, with a substantial amount of evidence which indicated the urgent need to replace the Cardinal of Chicago.

During late September, Cody received a phone call from Rome. The Vatican City village had leaked another piece of information – information well paid for over the years by Cardinal Cody. The caller told the Cardinal that where Pope Paul had agonized his successor John Paul had acted. The Pope had decided that Cardinal John Cody was to be replaced.

Over at least three of these men lurked the shadow of another, Licio Gelli. Men called him ‘Il Burattinaio’ – the Puppet Master. The puppets were many and were placed in numerous countries. He controlled P2 and through it he controlled Italy. In Buenos Aires, the city where he discussed the problem of the new Pope with Calvi, the Puppet Master had organized the triumphant return to power of General Peron – a fact that Peron subsequently acknowledged by kneeling at Gelli’s feet. If Marcinkus, Sindona or Calvi were threatened by the various courses of action planned by Albino Luciani, it was in Licio Gelli’s direct interests that the threat should be removed.

It was abundantly clear that on September 28th, 1978, these six men, Marcinkus, Villot, Calvi, Sindona, Cody and Gelli had much to fear if the Papacy of John Paul I continued. It is equally clear that all of them stood to gain in a variety of ways if Pope John Paul I should suddenly die.

He did.

Sometime during the late evening of September 28th, 1978 and the early morning of September 29th, 1978, thirty-three days after his election, Albino Luciani died.

Time of death: unknown. Cause of death: unknown.

I am convinced that the full facts and the complete circumstances which are merely outlined in the preceding pages hold the key to the truth of the death of Albino Luciani. I am equally convinced that one of these six men had, by the early evening of September 28th, 1978, already initiated a course of action to resolve the problems that Albino Luciani’s Papacy was posing. One of these men was at the very heart of a conspiracy that applied a uniquely Italian solution.

Albino Luciani had been elected Pope on August 26th, 1978. Shortly after that Conclave, the English Cardinal Basil Hume said: ‘The decision was unexpected. But once it had happened, it seemed totally and entirely right. The feeling he was just what we want was so general that he was unmistakably God’s candidate.’

Thirty-three days later ‘God’s candidate’ died.

What follows is the product of three years’ continuous and intensive investigation into that death. I have evolved a number of rules for an investigation of this nature. Rule One: begin at the beginning. Ascertain the nature and personality of the dead subject. What manner of man was Albino Luciani?

The Road to Rome

The Luciani family lived in the small mountain village of Canale d’Agordo,* nearly 1,000 metres above sea level and approximately 120 kilometres north of Venice.

At the time of Albino’s birth on October 17th, 1912, his parents Giovanni and Bortola were already caring for two daughters from the father’s first marriage. As a young widower with two girls and lacking a regular job Giovanni would not have been every young woman’s dream come true. Bortola had been contemplating the life of a convent nun. Now she was mother to three children. The birth had been long and arduous and Bortola, displaying an over-anxiety that would become a feature of the boy’s early life, feared that the child was about to die. He was promptly baptized, with the name Albino, in memory of a close friend of his father who had been killed in a blast furnace accident while working alongside Giovanni in Germany. The boy came into a world that within two years would be at war, after the Archduke Francis Ferdinand and his wife had been assassinated.

The first fourteen years of this century are considered by many Europeans to have been a golden age. Countless writers have described the stability, the general feeling of well-being, the widespread increase in mass culture, the satisfying spiritual life, the broadening of horizons and the reduction of social inequalities. They extol the freedom of thought and the quality of life as if it were an Edwardian Garden of Eden. Doubtless all this existed, but so did appalling poverty, mass unemployment, social inequality, hunger, illness and early death. Much of the world was divided by these two realities. Italy was no exception.

Naples was besieged by thousands of people who wanted to emigrate to the USA, or England, or anywhere. Already the United States had written some small print under the heroic declaration, ‘Give me your tired, your poor. Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.’ The ‘wretched refuse’ now discovered that disease, insufficient funds, contract labour, criminality, and physical deformity were a few of the grounds for rejection from admission to the United States.

In Rome, within sight of St Peter’s, thousands lived on a permanent basis in huts of straw and brushwood. In the summer many moved to the caves in the surrounding hills. Some did dawn to dusk work in vineyards at fourpence a day. On farms others worked the same hours and received no money at all. Payment was usually in rotten maize, one of the reasons that so many agricultural labourers suffered from a skin disease called pellagra. Standing waist deep in the rice fields of Pavia ensured that many contracted malaria from the frequent mosquito bites. Illiteracy was over 50 per cent. While Pope after Pope yearned for the return of the Papal States, these conditions were the reality of life for many who lived in this united Italy.

The village of Canale was dominated by children, women and old men. The majority of men of working age were forced to seek work further afield. Giovanni Luciani would travel to Switzerland, Austria, Germany and France, leaving in the spring and returning in the autumn.

The Luciani home, partly con

verted from an old barn, had one source of heating, an old wood-burning stove which heated the room where Albino was born. There was no garden – such items are considered luxuries by the mountain people. The scenery more than compensated: pine forests and, soaring directly above the village, the stark snow-capped mountains; the river Bioi cascaded down close to the village square.

Albino Luciani’s parents were an odd mix. The deeply religious Bortola spent as much time in the church as she did in her small home, worrying over her increasingly large family. She was the kind of mother who at the slightest cough would over-anxiously rush any of her children to the nearby medical officers stationed on the border. Devout, with aspirations to martyrdom, she was prone to tell the children frequently of the many sacrifices she was obliged to make on their behalf. The father, Giovanni, wandered a Europe at war seeking work that ranged from bricklaying and engineering to being an electrician and mechanic. As a committed Socialist he was regarded by devout Catholics as a priest-eating, crucifix-burning devil. The combination produced inevitable frictions. The memory of his mother’s reaction when she saw her husband’s name on posters which were plastered all over the village announcing that he was standing in a local election as a Socialist stayed with the young Albino for the rest of his life.

Albino was followed by another son, Edoardo, then a girl, Antonia. Bortola added to their small income by writing letters for the illiterate and working as a scullery maid.

The family diet consisted of polenta (corn meal), barley, macaroni and any vegetables that came to hand. On special occasions there might be a dessert of carfoni, pastry full of ground poppy seeds. Meat was a rarity. In Canale if a man was wealthy enough to afford the luxury of killing a pig it would be salted and last his family for a year.

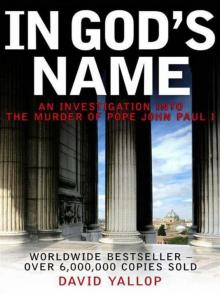

In God's Name

In God's Name